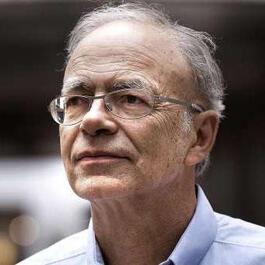

Peter Singer - The Life You Can Save

Peter Singer has been called "the world’s most influential living philosopher," by The New Yorker and Time Magazine listed him in “The Time 100,” their annual listing of the world’s 100 most influential people. He is DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, and laureate professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics, University of Melbourne. He writes a regular column for Free Inquiry magazine, and is the author of dozens of books, including Practical Ethics, Rethinking Life and Death, and Animal Liberation (which has sold more than a half million copies), Writings on an Ethical Life, One World: Ethics and Globalization, The President of Good and Evil (about George W. Bush), and The Way We Eat. His most recent book is The Life You Can Save: Acting Now To End World Poverty. In this conversation with D.J. Grothe, Peter Singer details how twenty-six thousand children die each day of preventable diseases and poverty worldwide, and contrasts this toll with the public's moral outrage over the blackest days in our history, such as 9/11/2001. He talks about the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth regarding the poor, and questions why most Christians today have seemed not to make ending world poverty a priority, instead focusing on issues such as abortion and homosexuality, which are not mentioned by Jesus. Singer argues that when people in affluent societies value even small luxuries more highly than saving the lives of the world's poor, that it is morally equivalent to standing by when one could easily save someone from drowning. He says that "if you're not doing something serious to end world poverty, that you're not living an ethical life." He suggests that much philanthropy, such as charitable giving to the arts, should be less of a priority than fighting world poverty. He recommends various aid organizations that merit financial support, such as Oxfam International, and highlights GiveWell, whose purpose is to evaluate the effectiveness of other aid organizations. He suggests that it is often more efficient for private organizations to administer aid than it is for governments to provide poverty relief. He argues against various challenges to his position: that giving to the poor may foster their dependence, that charity should begin at home, that the poor deserve their lot, and that our lack of concern about the world's poor may be a natural function of our evolved human nature to care primarily about our own kin. He argues that while his ethics is informed by the worldview based in the sciences and Darwinism, that it is not derived from Darwinism, and he argues against "Social Darwinism," and "the survival of the fittest." He explores the strategic implications that the demanding nature of his ethics has for its more widespread adoption in society. He talks about the meaning and sense of purpose that fighting to end world poverty may create in one's life. And he expresses the hope that skeptical and nonreligious people will become more motivated to fight world poverty, even without religious incentives, and that they will become part of a new culture of giving.

From "Point of Inquiry"

Comments

Add comment Feedback