Giving Poor Populations Money Lowers Their Birth Rate?

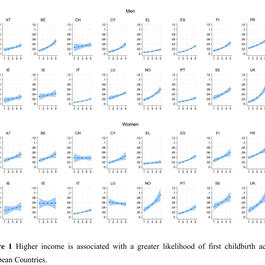

In this eye-opening discussion, Malcolm and Simone Collins dive deep into a shocking demographic shift happening in wealthy countries: the complete inversion of the traditional fertility-wealth relationship. For decades, poorer families had more children while richer ones had fewer. But starting around 2017, in nations with generous social services (free childcare, healthcare, education), higher-income and higher-educated people are now having MORE kids — while lower-income groups are having fewer. We explore: * Why universal free childcare and welfare might unintentionally reduce fertility among lower-income groups * How modern “poor” lifestyles increasingly resemble historical elite living (outsourced child-rearing, conspicuous consumption, work outside the home) * How modern “rich” lifestyles are starting to look like historical peasant life (homesteading, stealth wealth, focus on home/family, less external work) * The implications for fertility collapse, dependency ratios, and whether generous in-kind social services could accidentally “solve” collapsing birth rates by boosting high-earner fertility Backed by 2025 research from Western Europe, Nordic data, and real-world examples. Is giving people free services the unexpected key to higher birth rates among taxpayers? Or is something deeper happening with culture and household structure? Episode Outline What it means to be rich, and what it means to be poor, is fundamentally changing, and not like you’d think. Rich people are starting to live like poor people used to live, and poor people are increasingly live like rich people used to live And you can see this coming up in all sorts of places, but most notably in recent shifts in fertility This is a big deal and I think we should explore it. SETTING THE SCENE * In September, New Mexico’s governor announced that New Mexico will be the first US state to offer universal free childcare, regardless of income * Average household savings are estimated at around $12,000 per child, per year (major understatement; when we had just three kids, we were spending around $4K/month—so around $50K/year for a daycare with a terrible reputation) * This comes at a time when polling indicates Americans want the US to focus on measures like this to combat declining fertility rates * WHAT WE WOULD EXPECT FROM THINGS LIKE FREE CHILDCARE: * If the state covers major basic costs of having kids, rich people would have fewer kids as their standards for raising kids would be higher * Wynnell anecdote: $1M/kid/year * THE COUNTERINTUITIVE TREND * Starting in 2017, we’ve seen a shift in wealthy countries—that largely cover things like childcare, education, and healthcare—in which wealthier and more educated families are having more children than poorer and less educated families. * KEY QUESTION * Why does giving resources to poor people not increase their fertility proportionately to rich people? * WHAT PEOPLE ARGUE: * When the state doesn’t offer generous social services, wealthy families aren’t willing to pay for having kids (but somehow poor families are) * Having to work—as poor people do—competes with family demands * WHY I HESITATE * Wealthy people still work and have aggressive schedules * Wealthy people also generally choose to have kids in more expensive ways—i.e. Waiting until they are old and infertile and then having kids expensively—and they’re struggling with that cost * E.g. IVF is so expensive, people are traveling abroad to get it * E.g. One couple found a clinic in Bogota, Colombia “offering a dramatic price difference—a package of four IVF rounds in Colombia for $11,000 compared to around $60,000 for four rounds in the U.S. Medication costs were also less than half of those in the U.S.” * MY HYPOTHESIS * The issue is more that governments and societies are turning poor people into wealthy people—or at least people who live like wealthy people historically lived—and turning wealthy people into poor people (or at least people who live like poor people used to live) and that’s why we’re seeing the inversion * I’ll explain why at the end, but let’s go into the details first. First, a Caveat We’re talking about wealthy countries here, and wealthy countries (with one notable exception) have abysmal birth rates. @MoreBirths Thread The Thread: * Lower income had been associated with higher fertility but now that relationship has completely flipped in many developed countries. Higher incomes are now associated with higher fertility almost everywhere in Europe, for both men and women, a 2025 paper shows. * But this is only within countries. Across countries the correlation between income and fertility remains very negative. Wealthy countries continue to have far lower birthrates than poor countries. Also, fertility tends to go down for countries as a whole as they get richer. * Cool animation that amusingly resembles sperm: * /photo/2 But obviously as wealthy countries’ fertility rates are low, they need to work out what policies help to increase them. The Wealthy Country Shift We Must Investigate Back to this unexpected shift Historical and Current Trends For most of the 20th century, there was a negative relationship between wealth and fertility in Europe: wealthier individuals typically had fewer children while poorer families had more. However, starting around 2017, this pattern weakened and has even reversed in several prosperous European countries by 2021. In some places, the association is now neutral or even slightly positive. * Similar patterns hold when using education as a proxy for income: low-educated Nordic women and men now have the lowest fertility and highest childlessness (15-36% in recent cohorts), while higher-educated groups have stabilized near replacement levels (around 1.8-2.0 children per person). Variation by Region and Gender * In Nordic countries such as Sweden, studies show a clear positive connection between high lifetime earnings and having more children, especially among men. For women, the relationship shifted from women having more kids (up to women born around the 1940s) to positive or flat in the 1970s cohorts, with the poorest women now having the fewest children due to higher childlessness rates. * In Southern Europe, parental wealth is still related to lower fertility, while in Nordic countries, greater wealth is associated with higher fertility rates. Regional Differences and Welfare Regimes In European countries with limited social welfare support—such as lacking free childcare or universal healthcare—fertility rates among wealthier citizens generally show only a weak positive association or sometimes remain lower, especially in Southern and Eastern Europe. * In Southern Europe and some conservative welfare states (like Greece and Italy) with weak, higher parental wealth does not strongly compensate for limited public support. * In contrast, Nordic countries and regions with extensive social support show a clearer trend: high-income individuals, especially men, tend to have more children What Spurred Discourse About This: An Academic Paper A research note on the increasing income prerequisites of parenthood. Country-specific or universal in Western Europe? https://labdisia.disia.unifi.it/wp_disia/2025/wp_disia_2025_05.pdf (Brini, Guetto, Vignoli, 2025) TL:DR: They’re trying to argue that wealth is beginning to correlate with having kids more because “having kids is so expensive.” THEY ARE TRYING TO SAY WE NEED TO GIVE PEOPLE MORE MONEY FOR KIDS. Summary of Findings [not to be covered in podcast, but for show notes]: * Key Question: Has the role of income in enabling parenthood strengthened in Western Europe from 2006–2020, and are increasing fertility inequalities present between higher- and lower-income groups for both men and women? * Main Findings: * Higher individual income strongly increases the likelihood of having a first child for both men and women across 16 Western European countries studied; the effect is stronger and more widespread for women, especially in countries with robust welfare systems. * The role of income as a prerequisite for parenthood has increased over time: Income-based fertility gaps have widened, primarily due to declining birth rates among low-income men and women, not just rising births among higher-income groups. * Country Variations: * In most countries (France, Italy, Luxembourg, Sweden, Austria, Norway, UK, Belgium, Cyprus), widening fertility gaps are driven by declining parenthood among low-income groups—supporting the “increasing income prerequisites” hypothesis. * A few countries (Finland, Ireland, Greece, Spain) show weakened male income effects, suggesting evolving gender norms (”changing gender roles” hypothesis). * Only Portugal fits the “declining opportunity costs” hypothesis, with increasing parenthood among high-income women due to policy improvements. * Implications: Economic resources are increasingly critical for starting families, especially for women. Lower-income groups are increasingly excluded from parenthood, and the combined incomes of partners matter more than ever. * Evidence and Method: Analysis based on longitudinal EU-SILC data for individuals aged 18–45, modeling income (lagged two years), education, and employment status, with results robust across country and gender. * Sensitivity Analyses: The effect persists when considering partnered individuals and total household income, ruling out partnership exclusion alone as the explanation. * Conclusion: Financial barriers to parenthood have risen and become more universal in high-income countries. The income prerequisites of parenthood increasingly contribute to income-based fertility inequalities, with widening divides driven by falling birth rates among lower-income women and men. These trends are consistent with rising economic uncertainty, declining employment stability, and evolving gender roles. The financial stability needed to have children now depends heavily on both partners’ earnings, increasing disadvantage for those with lower incomes. Bottom Line: In modern Western Europe, having children has become more conditioned on income, and this new reality intensifies socioeconomic inequalities in family formation. The Generosity of European Social Programs It needs to be emphasized that the countries investigated in this academic paper already do A LOT to support parents. * I researched top, mid, and low-level providers of benefits in Europe and then color coded them; the vast majority of the countries they covered are top tier when it comes to social benefits. * The TL:DR is that these people are living the dream of what, say, American families say they want in terms of support, and yet it’s not apparently helping typical families of modest means have more kids. Top Providers of Social Benefits * Luxembourg: Highest per capita spending on family benefits; extensive free education and healthcare, substantial childcare support. * Nordic countries (Norway, Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, Finland): High expenditure per person, universal healthcare, free or highly subsidized education, and robust childcare systems. Denmark, for example, is noted for the most generous overall welfare package. * France: Leads in overall social spending, with nearly a third of GDP devoted to social services—free healthcare, subsidized childcare, and free higher education. * Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Ireland: All spend above €1,000 per person yearly on family benefits, maintain generous healthcare and education systems, and support families with substantial social programs. * Belgium, Finland, Sweden: High levels of social expenditure and strong systems of universal services. Mid-Tier Providers * Netherlands: Welfare support below the EU average, including less generous family benefits, though healthcare and education remain accessible. * Italy, Spain: Social spending is moderate; both provide universal healthcare and public education, though cash benefits and childcare support are less extensive than in Northern Europe. * Cyprus, the United Kingdom, Portugal, and Greece generally fall in the middle to lower tier of European countries for social benefits, with each ranking lower than Northern and Western European nations but Portugal notably ahead of Greece and Cyprus. * Note re: the United Kingdom: Around 23–26% of GDP spent on social welfare, average by OECD standards, but benefit value is low relative to wages, with notable gaps in unemployment and adult support. Countries with Least Generous Benefits * Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, Czech Republic: Lowest per-person spending on family benefits; limited state childcare, lower national GDP allocation for social protection, and constrained healthcare provisions. * Turkey, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina: Non-EU nations at the lowest end of the support spectrum, with minimal expenditure on social benefits per capita and more fragmented public service offerings. * Montenegro, Serbia: Limited social safety nets and public service funding; ranked low in comprehensive benefit provision. Are The Numbers Just Off? It should be noticed that some are arguing that surrey error and small sample sizes should make us question whether wealthy families actually have more kids. Lyman Stone on Fertility and Wealth Fertility and Income: Some Notes (published in April 2024) * Lyman Stone argues that Income reporting in surveys is unreliable for very small subgroups (e.g., $1 million+ households), so findings about ultra-high earners can be artifacts not robust trends. * Stone nevertheless makes some concessions: There is some evidence on causal ties between income and fertility: at least one study shows exogenous positive shocks to male incomes boost fertility, and there are many others using more quasi-experimental variation from sectoral or occupational exposures. But “male income” isn’t “income.” The figure the U-shapers rely on is family or household income. It includes male income and female income. * The big point he wants to argue is that non-wage income (rent, interest, welfare, etc.) may be pronatal, but earnings are not. * We have argued extensively that he is biased in favor of welfare, so of course he would want to say this. * Where we agree with Lyman Stone is that: * The relationship between income and fertility is highly dependent on culture * Stone points out that different cultural groups (e.g., Amish, Ultra-Orthodox Jews, Asian Americans) show very different patterns. * “Income X Culture → Fertility” is a more accurate framing than “Income → Fertility.” * Evidence shows that fertility is more closely tied to relative social status and income than absolute wealth or GDP growth. So What’s Going On? Top public arguments * Poorer families are less healthy * Poorer families are too busy trying to make ends meet to start a families * Poorer families have less flexible schedules and less work-life balance * Poorer families have less stable marriages/partnerships * Wealthier families have stronger social networks * Children are framed as luxury goods so kids aren’t an obvious part of life, but something you have if you can afford them One important takeaway: * We now have more reason to believe that social services and even money aren’t the solution to fertility (because women’s wealth doesn’t correlate with higher fertility in these cases; it’s just increased male wealth) What I really think is going on: * Poor people are becoming like wealthy people, especially in these countries * Kids being cared for outside the home * More ability to work * More work outside the home * More focus on material wealthy * Wealthy people are becoming more like poor people * Less focus on work, more leisure time * More work from home * Less focus on material wealth and conspicuous material consumption * Stealth wealth * Ballerina Farms * MAHA * More focus on autonomy and separation from society * Compounds * Charter cities * Permaculture, homesteading In short, this is a product of what happens within the household. Episode Transcript Simone Collins: Hello Malcolm. I’m excited to be speaking with you today because there’s this thing I’ve really been stuck on recently and I think I’m realizing that what it means to be rich and what we thought it means to be poor is, is fundamentally changing and actually inverting. And not the, the way you’d think. So, so specifically rich people are starting to live like poor people used to live, and, and poor people are increasingly living like rich people used to live. Malcolm Collins: You know, you just say this upfront and I’m like, oh my God, this actually checks out when I look friends. Simone Collins: Yeah. And, and you can see this coming in all sorts of places, which we’ll talk about. But most notably, and I wanna couch this in, in this larger context, you can see this most notably in, in recent shifts in fertility. And this, this actually is a big deal. It has pretty significant implications, and I want us to explore it. So let’s just dive right in. And, and I’ll start with the, on the fertility front, a sort of like premise setting thing to sort of get us into this thought experiment and like, whoa, what’s going on here? This [00:01:00] doesn’t make sense. In September, new Mexico’s governor announced that New Mexico will be the first US state to offer universal free childcare regardless of income, which is, that’s huge. Yeah. Average household savings are estimated to be around $12,000 per child, which checks out per year. And I actually think that’s a major understatement. ‘cause when we had just three kids, we were spending around. 4,000 a month, so around 50,000 a year as we had obviously stopped ‘cause it burned through our savings. And, and that was for the daycare with a terrible reputation. The daycare that Yeah. Malcolm Collins: This is a daycare that a bunch of kids died at. Simone Collins: Yeah. Yeah. Not, not the location our kids were at, but you know, Malcolm Collins: in New York. Simone Collins: Yeah. A very close location. Yeah. And, and this, this comes at a time also, and we’ve reported on this separately. When polling indicates that Americans want the US to focus on measures like this to come black declining fertility rates and not other things. They’re just like, I just pay for my childcare. Like, stay outta my life, but like, make it easier. So what you would [00:02:00] expect from things like for a childcare? I is, I mean this is what I would intuitively expect is if the, the state covers major basic costs of having kids. Malcolm Collins: Mm-hmm. Simone Collins: Then rich people. Are gonna have fewer kids as, as their standards for raising kids are higher, and then, and, and poor people, people of modest means for who this daycare expensive is. It’s, it’s huge, right? Like it’s devastating. They would have more kids. Yeah, so like the middle class and lower class people would have more kids and Rich, rich people would have still fewer kids. Like it wouldn’t affect them because, do you remember what your mom said about how much money we needed, like per kid, Malcolm Collins: per year? It was a million dollars per kid, right? Simone Collins: Yeah. She’s like, well, you need a million dollars in income per year. Per kid. Per Malcolm Collins: kid, Simone Collins: because she’s unhinged. But that, that is a rich person norm. Around kids, right? Yeah. So you just think that like, well, but rich people have really unsustainable standards around how much kids cost. You know, they have all these nannies and all the clothes and all the activities and like, they wanna fly around the world with them, so [00:03:00] they’re, they’re too expensive. They wouldn’t have more kids just ‘cause childcare is paid for, but No, no. And this is what’s so crazy. Starting in 2017, we’ve seen a shift in wealthy countries. That largely cover things like childcare and education and healthcare in which wealthier and more educated families are having more children than poorer and less educated families. Malcolm Collins: I don’t believe it. Simone Collins: No, it’s true. It’s true. Malcolm Collins: I don’t believe it. This is this. Simone Collins: I’ll show you the data. No, man. This is insane. So the key question is, why does giving resources to poor people not increase their fertility proportionally to rich people? Because that is a, that is a, like, this is so perplexing and what people are arguing. So it it, when you go into this and even when you go into like the academic research covering this inversion and this strange trend, they’re like, oh, well, I. When, when the state doesn’t offer generous social services, wealthy [00:04:00] families aren’t willing to pay for having kids, but somehow poor families are. They’re like, they’re literally arguing this and, and they’re basically arguing that basically having to work at all as poor people do, competes with family demands. But I, I hesitate to buy that at all because wealthy people still work and have aggressive schedules. Like we know this, we have a lot of wealthy friends, and they’re extremely busy, Malcolm Collins: and they’re also, oh, I don’t know. Simone Collins: Well, no, that’s, we’re gonna get to that, that that is true. ‘cause maybe that’s not so true. Also though, but Malcolm Collins: here’s what I don’t understand. Why are they giving money to poor people? Simone Collins: These are also legit questions, but also, like wealthy people have kids in more expensive ways, not just in that, like they wanna get them the nannies and the fancy clothes, and the fancy toys, and they wanna fly them everywhere and do things like that. But like they’re, they’re typically waiting to have kids in the, until they’re older and more infertile. So they’re more likely to need fertility treatments and need IVF and have more complicated pregnancies or even use surrogates, you know, it’s really common, [00:05:00] right? So like that would also make me think that they’re gonna have fewer kids. In fact, IVF is so expensive. People are increasingly traveling abroad to get it. And, and to, to the extent that we’re seeing major mainstream news outlets covering it. Recently Malcolm Collins: that IBF clinic that was gonna open the Philippines and do like embryo testing. Is that happening still? Simone Collins: It’s still happening, yeah. Did you Malcolm Collins: have a timeline on that for like, our fans Simone Collins: we’re under an NDA, so I can’t say anything. Okay. But once, once we have an update, we can share information. But like, CBS news recently did an article about it. They talked about one couple that found a clinic in Bogota that they were going to, that offered a package of four IVF rounds for $11,000. Which, you know, compared to like the $60,000 it would cost to do four rounds, then that’s on the lower end in the United States. That’s like really good. So my hypothesis here is that the issue is more that governments and societies are turning poor people into wealthy people, or at least people who live like wealthy people historically lived [00:06:00] and turning wealthy people into poor people, or at least the way that. Poor people used to live and, and, and, and we’ll, we’ll explore that in greater detail. But first I just wanna give a caveat and, and this can be really summed up well by a, a thread that, that more births did when covering this Malcolm Collins: Yeah. Simone Collins: This research, Malcolm Collins: you know, who’s gonna love this data, right? Is lineman Stone, Simone Collins: actually, I’m also gonna cover limestone had, actually, he didn’t chime in about this just as it came out because this was a 2025 thing. I’m gonna. I’m gonna look at W Stone has a take on this. He published in April of last year though, or like spring of last year. Okay. But in this thread more births explains a lower income has been associated with higher fertility. But now that the relationship is completely flipped, he writes, in many developed countries, higher incomes are now associated with higher fertility almost everywhere in Europe, both for men and women at 2025 paper shows. And we’re gonna look at that paper. His second tweet though, and this is important, but this is only within countries. [00:07:00] Across countries, the correlation between income and, and fertility remains very negative. Wealthy countries continue to have far lower birth rates than poor countries. Also, fertility tends to go down for countries as a whole, as they get richer. Also I kind of just wanted to, to show you this thread, just because one of the animations that shows basically the fertility of countries going down is to get wealthier. Literally looks like sperm. Look at, look at, look at the link. I just said, Malcolm Collins: what is wrong with you? Come on. You are so juvenile. Simone Collins: It’s thematic. It’s thematic. Okay. I just find that extremely amusing. Malcolm Collins: But swimming downhill. Yeah. Yeah. Simone Collins: There’s, there’s little sperm swimming downhills. They get, you know, wealthier, their fertility goes down. Along with their sperm motil, their testosterone levels plummet but obviously wealthy countries, fertility rates being low, it is important to be looking at. What we can do to increase fertility in these countries. And it’s pretty wild that now the wealthier increase poverty Malcolm Collins: people. Simone Collins: Yeah. Outside of, yeah, outside of that. So let’s, let’s look at this wealthy [00:08:00] country shift that we need to investigate. So for most of the 20th century, there was a negative relationship between wealth and fertility. In Europe, wealthier individuals typically had fewer children, while poor families had more. Everyone knows this. We talk about this a lot. However, starting around 2017, this pattern weakened. It’s been even reversed in several prosperous, and this is the important thing, prosperous European countries by 2021. In some places the association is now neutral or even slightly positive. And similar patterns hold when using education as a proxy for income. So low educated Nordic women and men now have the lowest fertility. In highest childlessness, 15 to 36% in recent cohorts. While higher educated groups have stabilized near replacement levels around 1.8 to 2.0 children per, what is Malcolm Collins: it in? Simone Collins: The Nordic countries. Malcolm Collins: The Nordic countries. Mm-hmm. So the Nordic countries is now the lower income and lower education you are as a man, the lower your fertility rate. Simone Collins: And, and woman. And woman Malcolm Collins: and woman. Simone Collins: [00:09:00] But here’s no, there, there are different, there are different, regional and gender variations that I, I, I am glad you’re, you’re pointing to this. Yeah. So in Nordic countries such as Sweden, studies show a clear positive connection between high lifetime earnings and having more children, especially among men. But for women, the relationship shifted from women having more kids up to women born around the 1940s to positive or flat. In the seventies, cohorts with the poorest women now having the fewest children due to higher childlessness rates in Southern Europe. However, prenatal wealth. Or sorry, parental wealth is still related to to, to lower fertility. Malcolm Collins: So in poorer countries, the poorer you are, the higher your fertility rate Simone Collins: is. Yeah. Yeah. Malcolm Collins: But in wealthier countries, the poorer you are, the lower their fertility rate is. Mm-hmm. And it seems to be correlated with the amount of social services that poor people are getting. Simone Collins: Yeah. Malcolm Collins: To sterilize the poor is to give them money. [00:10:00] Exactly. That’s why we’re giving poor people money. Ugh. Simone Collins: Yeah, they’re, they’re trying to stick. No, but seriously, in European countries with limited social welfare support like if they don’t have free childcare, if they don’t have universal healthcare, fertility rates among wealthier citizens generally show only a weak positive association or sometimes remain lower. Especially in Southern and eastern Europe. So in Southern Europe and some conservative welfare states like Greece and Italy with weak, higher parental wealth does not strongly correlate or compensate for limited public support. In contrast, Nordic countries and regions with extensive social support show clearer trend high income individuals, especially men, tend to have more children. And so what, what spurred this discourse about this in the paper, that more birth cited that just came out this year? Oh my God. Can you hear a text? Snoring? Malcolm Collins: No Simone Collins: sound ever. Oh my God. Malcolm Collins: You, you could put the microphone up to him. All the, the ladies [00:11:00] watching. Simone Collins: I, I think I, I’ve woken him up. Malcolm Collins: Oh, there. Oh, you woke him up. Simone Collins: Crumbs. Oh God, I, I, I just, when he snores, it’s the cutest son ever. But whatever I, the moment is passed. I ruined it. But so, right, so there, there was a paper that came out that, that discussed this trend that is, that is the whole spark of all this. And it called let’s see. It’s the, it is the sexiest and most catchy title of all research papers. Research note on the increasing income prerequisite parenthood country specific or universal and Western Europe. That is, that is the title. Not exactly the best, but the TLDR is, they’re trying to argue that wealth is beginning to correlate with having more kids, because having kids is so expensive. They’re, they’re, they’re trying to say, we need to give people more money for kids like that. That is literally their takeaway in this whole thing. [00:12:00] Mm-hmm. But here’s just like the, the key question they wanted to ask is, has the role of income in enabling parenthood strengthened in Western Europe from 2006 to 2020 and are increasing fertility inequalities present between higher and lower income groups for both men and women? And their main findings were that higher individual incomes strongly increases the likelihood of having a first child, both for men and women across 16 Western European countries that they studied. The effect is stronger and more widespread in women. Especially in countries with robust. Welfare systems. The role of income as a prerequisite for parenthood has increased over time. Income-based fertility gaps have widened primarily due to declining birth rates among low income men and women, not just rising births among higher income groups. So this is important, as you said, right? The way to sterilize poor people is to give them resource Malcolm Collins: UBI would do so much harm to fertility rates from what we’ve seen in the data Simone Collins: well, but especially among poor people. And that’s a really crazy thing [00:13:00] because you’d think like. Oh, well this is all, and that, that, that is what is constantly being argued, right? It’s like, well, we’re, we’re not the rich people in this country. We can’t afford to have kids. But what’s clearly shown in this data is that’s totally the opposite. Like, that is not at all how this is gonna work, which is, is it just so surprises me. And, but what, what also really surprises me is that the researchers are trying to argue. That this is just because it’s so expensive to have kids. Malcolm Collins: Well that actually isn’t a terrible argument. So if you’re thinking about, Simone Collins: explain this to me. The Malcolm Collins: amount of aid in the United States that poor people get around kids, it’s just comical compared to middle class people. Simone Collins: That’s true. That’s true. Malcolm Collins: Yeah. And, and, and, and middle class people can actually be priced out of having kids, whereas it’s very hard to price a poor person out of having kids in the United States. Simone Collins: That’s true. And for context in the United States. Because we, we did really extensive research on this to try to create like sort of an index of resources for parents [00:14:00] because we thought there would be more for just like your average, normal parent, but basically if you’re at or below the poverty line, healthcare is taken care of for, for kids and typically their parents. Two, or at least their mothers food assistance, childcare assistance, often housing assistance, often heat and electricity assistance. So you really get levels of subsidies that you, you would otherwise just expect in like the wealthy Gulf States for all. Citizens which is insane. Like just be impoverished. And, and there are many families in the United States who actively game the system to create the appearance of poverty just to get access to these resources because they’re so compelling, which is not the best, but go on. Malcolm Collins: No, I mean, you’re right. And I was also telling you about this earlier today, which I didn’t know about. But like true poverty doesn’t really exist in the United States. And I know that this is an offensive thing to say. I was point out to you that, for example, starvation in the United States, it’s [00:15:00] virtually just doesn’t happen. It happens to like 150 people a year or something. Simone Collins: Mm-hmm. Malcolm Collins: And almost all of them are elderly people or people who can’t move in some way. Like there, Simone Collins: right, like if it wasn’t the starvation, it would be bedsores or like. Literally they’re like their dogs eating them alive or something. ‘cause they can’t move. It’s, Malcolm Collins: yeah, yeah, yeah. They’re stuck at home and nobody’s bringing them food. Like, if you can go out and get food, you’re, you’re gonna be okay in the United States. Simone Collins: Yeah. And I wanna show you actually, so the, the, the research study that, that did, these graphs and correlations of between. Being more wealthy and having more kids. I was like, just how generous are all these countries that we’re looking at? So first I just looked at all the graphs and then , I sorted the European countries that they looked at in this research, Okay. By just how generous they were in terms of their social services. And I, I, I color coded them. So red is most generous, and orange is, is a slightly middle, like mid-tier, generous, like. They don’t support as much of healthcare and education and and childcare, and then yellow is least [00:16:00] generous. And pretty much the vast majority of the countries that they looked at here were all extremely generous countries. Even in the ones that are yellow circled, like the UK I circled in yellow, because it is, it is generally considered to be a little bit weaker on social services. Keep in mind, the UK still has the NHS, it has nationalized healthcare, and the caveat with the UK too is that the social services in the uk. Skew toward children really heavily. So the emphasis is more on like giving people citizens a really strong start. And like being Malcolm Collins: so yellow means a lot of social Simone Collins: services. It’s the weakest social services. Red is the strongest. Weak, Malcolm Collins: okay. And Simone Collins: red is, so, the vast majority of the countries that this study looked at are extremely generous in their services, meaning that this really does. This is about countries providing very, very, very generous social services. Basically just like free childcare, free good healthcare and free education. A among other things. So that’s, that’s, that’s it. Just, [00:17:00] it needs to be emphasized that the country’s investigated in this academic paper. Already do a lot to support parents. Makes sense. And I can go into it like some, some examples. Luxembourg has the highest per capita spending on family benefits. It has extensive free education and healthcare, substantial childcare support. The Nordic countries like Norway and Denmark and Iceland and Wheland and, and Finland they have a really, really high expenditure per person universal healthcare for. Free or highly subsidized education and robust childcare systems. Denmark, for example, is noted for the most generous overall welfare package. France leads in overall social spending. Nearly a third of their GDP is devoted to social services. Oh my Malcolm Collins: God. Simone Collins: Free healthcare, subsidized childcare, and free, free higher education in Germany and Austria and Switzerland and Ireland. All spend above 1000 euros per person yearly on family benefits. Maintain generous healthcare and education systems and support families and have. Very substantial social programs. So [00:18:00] again, like this is, we’re talking very generous. This is, this is an American’s dream in terms of what we keep asking for. Yeah. I just wanna emphasize again that this is just. It’s just ridiculous. Malcolm Collins: Oh no. Are you saying we need to be socialists now? Simone Collins: I’m not. And speaking of socialists, did someone say socialists? I, I wanna bring lineman stone to the chat. So lineman stone, actually, so one thing that we’ve, we’ve talked about in the past and that anyone who discusses fertility talks about is this U-shaped curve in fertility that’s very often discussed, right? Which has to do with income. And it’s this, the famous U-shaped graph that that shows fertility levels. Being really high among those who are impoverished. And then for the middle class, it just plummets. And then when you see incomes above $500,000, per household or whatever then it, it goes up again. And so like, oh, well, having a big family is just a super rich person thing and a super poor person thing. And Lyman Stone in an article that he [00:19:00] published in April 24 called Fertility Income, some Notes he argues that income reporting in surveys is unreliable. For very small subgroups that that is to say like 1 million plus households. And so he wants to say that, that the findings about ultra high earners can be artifacts and not robust trends. Oh, Malcolm Collins: so he doesn’t think that high earners actually have a very good fertility. Simone Collins: Yeah. He thinks that like, because so few people are in that income bracket and also responding to surveys that like probably what we’re seeing is like someone accidentally filling in the wrong. Thing on a survey. Like just the error. Yeah. And, and that’s, it’s, it’s, it is a legitimate. Concern. But he nevertheless does make some concessions. He, he says there’s some evidence on, on ca causal ties between income and fertility. At at least one study shows exogenous positive shocks to, to male income boost fertility, and there are many others using quasi experimental [00:20:00] variation from sectoral or occupational exposures. But he also argues male income is an income, the the figure, the U-shape. Advocates, essentially, he says rely on for fa is for family household income. It, it includes male income and female income. So that he, he thinks that’s not the thing, like really the thing he would encourage people to look at, and I don’t think he’s wrong. Is me relative male income that men, men doing disproportionately better. Mm-hmm. Seems to correlate more. And that even shows up in a lot of this more re recent research that I can’t remember who it was when I was going into some more of the, the ephemera of this discourse. People were pointing out that when you look at, when you break out female. Fertility in these countries, women with higher wealth had higher fertility, but if they had just higher income, they [00:21:00] didn’t, it was sort of like a neutral thing. Okay. So essentially like if you’re working your, your your fertility’s not gonna be higher if you’re a woman. And that makes sense because if you’re working and you’re a woman, it’s, it’s kind of harder to have a ton of kids and, and we’re gonna get to that. So, so. The, what the public is arguing in terms of what’s going on here, because that’s what we really wanna talk about here. Mm-hmm. They, the public argues that poorer families are less healthy, poorer families are too busy to trying to make ends meet, to start new families. Mm-hmm. Poorer families have less flexible schedules and they have less work-life balance. And so it’s harder to have kids or more kids. Poorer families have less. Stable marriages and partnerships. So they’re, they’re may be less likely to even have a partner with whom they can have kids consistently. And that wealthier families have stronger social networks. So they have, you know, maybe, you know, grandparents that are wealthy and available, they can take care of kids. They’re more comfortable having more kids. Malcolm Collins: Yeah. Simone Collins: And, and they also frame. [00:22:00] Children as luxury goods. And, and society has largely framed children as luxury goods. Well, I Malcolm Collins: also think there’s been a, a cultural shift among some wealthy groups. Yeah. Like especially you’re talking about ultra wealthy groups, which we hang out with. Having lots of kids has become quite the flex. Simone Collins: No, but even I would say among. All levels of society, except for like some religious communities. Kids are kind of seen as this thing that you do if you can afford them, and they’re a luxury product, but they’re not something, they’re, so you don’t have them unless you can afford them. You don’t have them unless you have your stable career and your house and everything else. I, Malcolm Collins: you know, walk through a grocery store with five kids. I feel like Prince Ali, like. Yes. And they’re all Simone Collins: dressed Malcolm Collins: the same as me, and they’re, and they’re marching in line, and I’m like, Simone Collins: n in her parade. It so feels like that. It really does. No, there’s you, you, there’s Malcolm Collins: everybody comes to look at us and you’re like, yeah, I got, I got five kids money. Simone Collins: Yeah, no, it really, it really does feel that way. But, but I mean, so I, I think those are legitimate things. [00:23:00] But what I think is much more interesting here is that poor people are becoming like wealthy people in, in these countries used to live. Kids are being cared for. By staff. They’re being cared for by by, by these childcare facilities. Mm. They’re being cared for by paid people. And, and, and, and there there’s more work outside the home. People are leaving. The home to go do things just like Lords used to go to Parliament or like go out on their trading ships or something. And, and there’s more, there’s more focus on material wealth, on conspicuous consumption, on, on, on showing other people how fancy you are, whereas the wealthy people we know are really starting to behave a lot more like surfs. Did in the past. Yeah. Where like there’s less focus on work and there’s more focus on really like. Focusing [00:24:00] in on industry of the home. There’s more work from home and within the home. And there’s less focus on material wealth and conspicuous material consumption and more stealth wealth. Like look at, look at the rise of stealth wealth. Look at the rise of, of, of influencers like ballerina farms where like they’re very, very wealthy. They, they’re living on their, like homestead farm, and they’re living like a corporate family, and the kids are shoveling manure. And, you know, they’re, they’re, they’re harvesting their own food and pumpkins and making meals from scratch. You know, they’re living life like surf. Yeah. And then like the whole Maha movement is like that too. You know? It, it’s very much like back to the land, back to the homestead, you know, very, very crunchy, very like no brand names on anything. And there’s a lot more focus on autonomy and separation from society. There’s this retreat from society. We’re not, there’s no balls, there are no galas, there’s no, like, you know, going out and fronting to people. It, it’s very, it, it’s very [00:25:00] isolationist. People have their, Malcolm Collins: there are some stone balls and galas, like when we go to Austin, we often go to like a, a gala or something Simone Collins: sometimes. Yeah. But it, it’s, I would say it’s, it’s pretty unusual. It’s mostly people retreating to their, if they’re really wealthy, I mean Sure. Like Peter Thiel may show up at hereon, but then it goes off to his, like New Zealand compound. Yeah. Or you know, like these other people. And then they disappeared to some, you know, to prospera to their charter city or to their like homesteading, permaculture. Farm thing. You know, like in, in short, I, I, I think in the end that so much of fertility, again, as you’ve always said it, it’s about how your household is composed and where you get your services. You keep saying fertility started to drop with the industrial revolution first when men left the home and then when women left the home and children left the home and every, all the services left the home and because. Now what being wealthy is, is it’s more about everything is coming back into the home. You [00:26:00] are able to see this rise of fertility again within the home because there’s, there’s value in it and there’s the time for it and the resources for it. Whereas for the. For those who are poor now, who are now living more like wealthy people who are getting DoorDash and delivery, they, you basically have your servants and your livery and, and your conspicuous consumption. And, and you know, the, all the staff that serves you. Much of it, government subsidized. Now, it doesn’t matter though. It doesn’t matter if it’s your own wealth or the government’s wealth when you have the staff, when things are provided from without the home when, when there isn’t this beating heart of your hear and your family. Your fertility drops. And because we’re seeing this inversion, that’s what the Malcolm Collins: best way to ize the core is to give them money that, that works for both parties. Simone Collins: Everyone wins. I mean, this, I think this, this does have interesting implications when it comes to fertility ratio cascades, because as we point out, this is not a warm bodies problem. This is a taxpayer problem. And, and so [00:27:00] what you really want, what if, if you’re a country that’s really concerned about not being able to pay for really essential social services for all these life saving. Food programs and, and even the childcare and the healthcare and all this, you need people who are gonna generate a lot of tax revenue to pay for it. And the fact that the people who generate a lot of tax revenue are now the ones having more kids power to the people literally power to like money to the people like that, that is a, a good thing. So could this be the solution? Like, are we already seeing like. Because we, I, I, I don’t think we expected this, right? We didn’t expect that like paying for people’s lives would, would actually solve fertility cascade problems. Is this kind of like, I mean, on one hand it doesn’t solve the problem ‘cause poor people aren’t having more kids. But does it solve the problem because. Rich people are having more kids. I mean, it kind of, you’re doing two things, right? Like you’re, you’re, you’re, you’re reducing the population that is most [00:28:00] dependent on these services, thereby maybe reducing the financial load while increasing the population that, that subsidizes these services, therefore increasing revenue. Like is this actually a subversion of trends? That means the problem is gonna be potentially solved. Malcolm Collins: I, Simone Collins: you don’t know. Malcolm Collins: So my question for you is, does this make you more socialist in your politics? Simone Collins: You know, my views are evolving on this actually. Because I. What we found and this, this has been confirmed also, like Scott Alexander I think mentioned this recently too, so I’m like, okay, this isn’t just us. Basically. While cash transfers seem to do a lot of good in really impoverished countries, it’s pretty clear that things like universal basic income and cash transfers cause harm in developed countries, right? They’re not good. However, it does appear to be that providing in kind services. Like free childcare education, sometimes [00:29:00] housing can actually cause pretty beneficial effects or at least neutral effects in developed countries. Yeah. We looked at this in the Gulf States, like, well, it didn’t seem to necessarily, it didn’t, it didn’t create thriving societies like the Gulf States aren’t exactly known for their innovation and, and their. You know? Malcolm Collins: Yeah. Simone Collins: Thriving, whatever, like they’re doing all right. Like, right, like there’s some basic cool people. Their fertility rates are decent. In, in some cases, not, not at all, but like Malcolm Collins: in some cases Simone Collins: it could be worse, right? But like, it’s not terrible. So I’m kind of warming up to the idea of providing in kind services, not money. People don’t get to choose, like you don’t just get your cash transfer. But in kind services, and this is also saying, I was just talking with you about this today because right now SNAP is being discussed a lot. It’s, it’s a form of food assistance in the United States where you get basically a debit card, like money is loaded to your card and you get to use that on a bunch of foods and a lot of people are just spending it on junk food. There’s this [00:30:00] other program in at least a lot of states called wic women, infant and Infants and Children. It’s for pregnant women, infants and children under five years old that meet certain requirements. And instead of providing money, it will cover very specific healthy foods. Like it will buy you a gallon of milk and a dozen eggs and a whole grain, and $26 worth of vegetables per child. And like some cheese, like, like the whole Malcolm Collins: food. This is, this is also made me realize. There’s another solution to fertility collapse that I had never considered before. Simone Collins: How’s that? Malcolm Collins: Which is you can fix the problem of a dependency ratio cascade within a country. So obviously you can do it by keeping the population stable as it exists right now. Simone Collins: Yeah. Malcolm Collins: But you could also do it just by stopping poor people from having kids. Simone Collins: Well, and, but these do that, but in like a very kind way. God, no, we’re not talking about steril. No. Malcolm Collins: [00:31:00] Sterilized. No, this is Simone Collins: getting way too close to eugenics and I don’t, Malcolm Collins: like, I didn’t say this is a good, I’m, I’m not saying it’s a good idea. I’m just saying it would solve the problem. Because. What you’re dealing with in a society is you know, the, the, the elderly are almost always on the government doll. Right. You know, so that’s why you get the fertility ratio cascade because too big a proportion of society is elderly. Simone Collins: Yeah. But Malcolm Collins: you have poor people who are also on the government dole. Yeah. And if you could remove them as a segment of the population Yeah. Then pretty much, no matter how many elderly people you got, it would be a, a lot more to tip the scales of the system. Simone Collins: Yeah, no, I mean, anyway, this has just been very thought provoking for me, and text now needs to eat, so I gotta go run. But like, Malcolm Collins: I love you Simon. Simone Collins: Thank you for humoring me on this. I’m very Malcolm Collins: excited for my, or whatever it’s called, the Simone Collins: ka ka. Malcolm Collins: Whatever. Simone Collins: I, man, it’s Malcolm Collins: tasty. It cook into oil again. That was really good. Simone Collins: And do the fried egg, Malcolm Collins: I might use a little bit more [00:32:00] oil and then scoop some chili flakes in. When you cook, cook it as well. Simone Collins: Oh yeah. Chili flakes. Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. I think it could use some chili flakes. Malcolm Collins: And then no other notes was really good. I might do two eggs today, actually. Simone Collins: I asked you about two eggs, but you said the serving was fine, but two eggs. Malcolm Collins: Yeah, I’d be more greedy with the eggs if I had two of them. And they were so good. Simone Collins: And then let’s just try two eggs. It’s from our coop man, and I’m so glad you’re like actually enjoying some of our coop eggs. Okay. I love you and I’ll see you too. I Malcolm Collins: love you too. Simone Collins: You’re amazing. You’re amazing. So pretty. , I know what you do. You’re just gonna set up your Korean romance manga right to the side of the screen. Malcolm Collins: I actually don’t even have my, I need to get my phone. Simone Collins: You nerd, but hurry up. Malcolm Collins: Simone, I have to know what happens. Simone Collins: Pull it up. Pull up web tunes. Don’t worry about it. Malcolm Collins: I have to know what happens to the, the Empress. Simone Collins: Yes. Malcolm Collins: Simon Simone, I have to know if Simone Collins: the, we really, really need to on like, Malcolm Collins: come on Simone Collins: Patreon and Substack. But you’re your [00:33:00] secret list of amazing romance Manga. Malcolm Collins: We’re the biggest nerds in the world and I think that when people first came to our podcast, they were like, wait, you guys can’t be like, at first they were confused ‘cause they’re like, you look. Too nerdy to be Republican, like, and, and then it was like, you gotta fashion yourself as like a non nerd, like get buff and like look a lot nerdy and it’s like, Simone Collins: oh, you gotta lift bro. Yeah. Malcolm Collins: And it’s like, I, but this is, this is. I am nerd from front to back. That’s my, Simone Collins: this is base camp. Like, do you guys understand what camp is? Is this an old person thing? Like, are, is everyone too young to understand what camp is anyway? No, Malcolm Collins: but imagine I come on and I am like really trying to look like, like, like cool. Stuff. Simone Collins: Think he’d be so cringe. Malcolm Collins: It’d be, I’d be so cringe. It’d be like Asma Gold doing that or something. No, I love ASM Gold recently went viral. I don’t know if you saw, for showing that he eats just junk food all day and like sodas Simone Collins: all day, he’s always shown that he eats just junk food all day. I think the secret is that he walks to [00:34:00] the seven 11 to buy the junk food and as long as, Malcolm Collins: no, it’s, he eats it in moderation. Simone Collins: Me too. Malcolm Collins: And, and that’s the thing. You can eat whatever you want, you know? Simone Collins: Yeah, like that famous twine diet guy. The professor. Yeah. Who showed that like, on like pure junk food, you could lose a ton of weight. I think actually multiple people did. ‘cause after also supersize Me came out, I think a high school teacher demonstrated that you can lose a lot of weight eating only McDonald’s, something like that. I, I can’t, I can’t remember. If Malcolm Collins: you are struggling with weight loss, my suggestion would be as is my suggestion for everything is get Naltrexone look up the Sinclair method and Simone Collins: it’s, yeah, it’s less expensive than LPs. So, Malcolm Collins: yeah, it’s, it’s less expensive than the other things. And it’s way healthier for you than like, Simone Collins: Oh yeah, that’s true. I mean, like as, as much as it can be. Naltrexone can, we’re not giving medical advice by the way, as much as naltrexone can be hard on the kidneys. GLP one inhibitors are. Which is what they’re right is, is that they, they are very hard on your digestive system. The, the side effects are really intense for people. Malcolm Collins: Yeah. [00:35:00] Naltrexone is a little bad on the liver. But every, all the other things that it cures, like alcoholism and obesity Simone Collins: did, dude, even gambling. Gambling is hard on everything, man. And gambling way Malcolm Collins: harder. Really Simone Collins: Big problem. Malcolm Collins: Harder. Well, and, and if you, if you have a problem with, with being too sexual like you’re Simone Collins: Yeah. Sex addiction. Food addiction, gambling. Of porn addiction. Like all these things can be’s Malcolm Collins: incredibly effective and I just hate that it’s not more known about. Simone Collins: Yeah, seriously, Malcolm Collins: it’s, it’s, it’s one of the Simone Collins: biggest, but y’all can read Katie Herzog’s book, I think it’s called Drink Yourself Sober. No, that’s not what it is. I can’t remember what it is, but check out Katie Herzog’s book. She wrote about it in depth. And she’s really unhappy with the amount of book sales. Malcolm Collins: Yeah. It’s really sad. Well, she get like 12,000 into sales or something. Simone Collins: Yeah. Like just Yeah. A abysmal. And she put a lot of work into the launch and interviewed with all the best platforms. Yeah. I mean, but on, on background. And she didn’t wanna name you because you’re too polarized. Oh. But whatever. By, by Katie Herzog’s book. We, we like it, we like blocked and [00:36:00] reported. Yeah. I met Katie Herzog and, well, I think, I think Jesse Single just. Billy doesn’t like us there. He stopped responding to you. Come Malcolm Collins: to our parties. And now Simone Collins: he’s like, I know, but also I think he’s he’s a little, a little Trump derangement. Yeah. I mean, Katie Kza is too, but she responded to us at least. I think she cares less. Anyway, we’ll get into it. I love you. Here we go. Ready? Malcolm Collins: Okay. Speaker: Wait, did you say this was the best Christmas ever? Yeah, I think so. I leave my and put this in my bedroom. This, what’s the one too? Well, we’ll go up and put them in your bed for future day decorations. You like ‘em guys? Yeah. Let’s go. Let’s go. Mom. Let’s go. Yeah, you’re super excited. Stall it right now. Yeah. Let’s open up your presents so you can play with those and then tonight we’ll put them in to start future day. Okay. Does that sound good? Yeah. Okay. If you safe right here [00:37:00] for now. My Tian, you hand it to me and I’ll make sure it goes to your bed. My. Honey, your T Rex’s name is honey. He’s gonna be the best dog for, oh, do you want milk and cheese? What are the colors for F Day? No. What does T-Rex want? What are the colors for F today sandwich Today, he wants to eat sandwiches. I. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit basedcamppodcast.substack.com/subscribe

From "Based Camp | Simone & Malcolm Collins"

Comments

Add comment Feedback